On Stage, On Country, In Community: Jimmy Kyle Shows Care

“My old people said to me, very simple, say it straight.”

When Thungutti storyteller and musician Jimmy Kyle frontman of the band Chasing Ghosts, gets on stage there’s a staunch ferocity with which he delivers his messages, when we are sitting in the green room at the Northcote Social Club joined by drummer Benny Clark and guitarist Josh Burgan there’s a sense of calm before the storm that is a Chasing Ghosts live show. Jimmy goes in depth on the themes of their recent album ‘Therapy’ for which they are only a couple of hours away from delivering a hometown Naarm (Melbourne) show.

A COMMUNITY OF CARE

There’s an intrinsic sense of kinship and camaraderie that is shared between each band member, grounded by a respect for each other. Jimmy describes it as, “a pull and push of tension between wanting to perform well and being really prepared and then just letting it happen. You go into war with these other people on your team, and you share the bond of whether you sink or swim together. Then if there's a stumble in the band, it's the other guys that cover for me, and if they have a stumble, hopefully I can cover for them.”

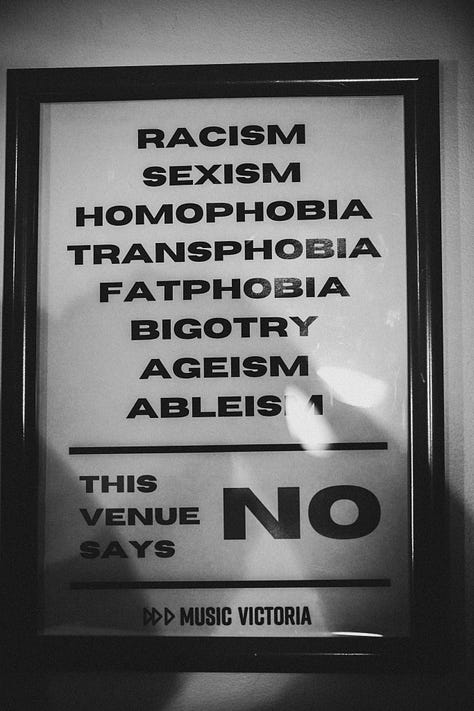

In my time with Jimmy he unpacks the same messages that he delivers in the live setting and on the record however person to person, without the layers of performance, there is an overpowering sense that what he says on stage he really means. Jimmy encourages conversations around some of the tougher issues facing his people and other marginalised groups around the world, approaching it with care and sensitivity it needs, “I think most people who are Chasing Ghosts fans are pretty staunch allies to the Aboriginal community and to the trans community and to the queer community”. The concept of community is central to Chasing Ghosts; it is something that they try to foster, “a community of like minded people”.

Music is a form of connection for Jimmy Kyle. He forms connections through the music community and through the communities he belongs to as a First Nations man.

Community is the bringing together of people, looking out for each other.

“I got inspired by those people, and I became very much a DIY person, and more about the culture of the music industry and scene and people and community, I guess is the main word I'd use, the music community.” The community that the band hopes to create at the shows is a safe and welcoming space for all.

He says that so much of the music he makes and the messages that come across in it, is grounded in who he is as a person, “being an Aboriginal man obviously has a lens I see the world through that is probably going to be different for each Aboriginal person. Even though there's a thread of common experience. It's going to be unique to my experience.

“I'm not from the central deserts, I've lived the last 15 years in urban areas, but I did grow up in the bush, in regional areas, and grew up with learning language and later into when I became an adult and I’m continuing to learn more about culture.

It is apparent for Jimmy that he finds his strength to be able to deliver the messages he does because he is strong in culture and knows he has the backing of his community. He finds strength from belonging. There is much to be admired in Jimmy’s approach to lifting others up with him but there is also a resonance there, as Blakfulla’s we do exist in communities whether that be where we live or the clan or Nation we belong to. There is a strong sense of responsibility to community, to the people we are in community with but also to the Country we are on.

CONNECTION TO PLACE

Jimmy shares that when he first moved to Naarm, he sought out community, especially Elders, and he did the same with where he now lives in Kanamulaka, Lutruwita ( Launceston, Tasmania), explaining when he came to live in both places, ”the first thing I did was introduce myself to the Traditional Owners and asked if I can work on Country.” This is a powerful act of respect for who’s Country he is living on, and that respect flows through everything that Jimmy does in the place where he is living. What is important to remember is the respect for the Country that we are on, continual learning of the stories of Country, often times stories of strength and resilience that go back thousands of years.

Jimmy has a deep love for Naarm, so much of the band’s history is in this city. It is the fabric of the rich tapestry that is the Naarm music community which Chasing Ghosts are stitched into, despite members living in different states they still refer to themselves as a Naarm-based band. Jimmy jokes about “Melbourne terrace house indie punk” which he believes many bands can be branded with but is best exemplified by Smith Street Band who have taken Chasing Ghosts under their wing as support on numerous occasions.

Jimmy loves this city for its incredible live music where you can go to multiple venues on any given night and see world-class local musicians on the stages, but not only that those that go to these venues talk of the warmth of the community, adding to this he says, “there's something about living the lifestyle here, where you're surrounded by mob, artists, thinkers, people that are expressive and creative, that help you to be around it and to understand it.”

Jimmy also has a deep love and respect for, “the contemporary Melbourne Aboriginal community, which is made up of the Traditional Owners of the Kulin Nations, and lots of Victorian Aboriginal people, lots of Aboriginal people from all over Australia, and how well people here work together. Like any other Aboriginal community, we have hurdles and obstacles, both internal and external, but there is something quite special about the Victorian Aboriginal community.

“It's highly informed, it's highly educated and there’s a lot of trust between the Aboriginal institutions and their community members. And those things definitely have informed the way that I think about the place.”

Though we’re here to talk about the new album ‘Therapy’, I think back to the storytelling on ‘Hometown Strangers in an Urban Dreaming’ from 2021’s ‘Homelands EP’ where he sings about an encounter which takes place “down by the Grace Darling” on Smith Street firmly planting the listener on the street as it vividly explores the tension that exists between non-Indigenous Australia and Indigenous Australia but in such a localised way.

In a similar way ‘My Bingayi’ and its accompanying film clip, one of the most powerful moments on ‘Therapy’, is set on the lands of the Palawa and Pakana Peoples, Lutruwita/Tasmania. It weighs in on the problem that Australia has with men using violence; rather than talking down or alienating men, it works to show there is another way whilst holding them accountable. Jimmy explains that when he moved there, “first thing I did was build relationships with the Traditional Owners- my partner is also a Traditional Owner from down there, so is my son and so doing projects with mob. I guess the thing is, wherever you can collaborate with mob, and in particular your own mob, that's where the magic happens.”

As has been explored throughout, Jimmy is drawn to community and finds much fulfillment from being part of communities and so tries to do this through his music but also in general life, “wherever I am that's I'm always going to sort of find myself somewhere between mixing with mob and a few musos, that's kind of always been the people that I orientate to, is probably people I can see myself in to some degree.”

The power that Jimmy has with the messages that he conveys through music shows he finds strength from knowing that he is standing on the shoulders of giants. He belongs to the oldest continuing culture in the world and makes music in a genre that has had some strong outspoken individuals and bands.

He shares how he has been inspired by DIY punk culture and the likes of Henry Rollins, but also the personal mentors that he has had throughout life. “I’ve had brilliant mentors. I had a lot of black mentors, and a lot of women, and those mentors gave me great insights into what the future might be and what's important and what the past has been.”

THE NEED FOR TRUTH TELLING

Jimmy uses his music to connect with people, to spread messages for positive change, and to insist on the power of truth telling. This is something that is etched into the very essence of Chasing Ghosts as a band, and also Jimmy’s worldview. “My old people said to me, very simple, say it straight. I try to be considerate and mindful, but my goal is to articulate the truth as I see it, and as many of my community members and non-Indigenous allies would also see it.”

There are many systemic issues as to why First Nations people in this country are often the ones doing it toughest but as Jimmy explains it can all be traced back to events that occurred roughly 250 years ago when colonisation began here. Jimmy asks the question, “what country can go from The First Fleet, skip 70 years of history, and go to the bloody Gold Rush and not be curious about what happened in that 70 years? How did Aboriginal people end up at the bottom of society?” The Frontier Wars, massacres, the forced removal of children and government policies which intended to eliminate Aboriginal people from this country.

Jimmy is staunch in the need for all Australians to know the true history of what took place on these lands. He is also very clearly articulates that there are systemic issues which started then and continue to today, “The issue is all the things that were denied to people, and the biggest one being empathy, that empathy has been denied to First Nations People, and the idea that this is all in the past, and it doesn't have a contemporary impact. I'm talking to you in the colonisers language, in a foreign language. A lot of Australians would never consider that English is a foreign language.”

Jimmy challenges how Aboriginal people are pushed to the margins of society and the monopoly of ‘Australian identity’, he says, “Even the terminology around us, our languages aren't Australian languages. They're Aboriginal languages… If they were true patriots, they’d be funding Indigenous languages. They would want to learn Indigenous languages.”

For Jimmy, the minimisation of Aboriginal sovereignty is like the minimisation of a victim’s story in an assault case. When people say things like “oh, well it could have been worse”. An attempt to minimise the impact that he has had is a deliberate refusal to empathise.

He draws comparisons with Ireland and other colonised places around the world, where Indigenous people still sit at the bottom of society. “Point to the country on the planet, out of the 195 countries on the planet, point to the one where those who have been colonised are doing better than the colonisers who colonised them. Show me a country where the Indigenous people do better than the colonisers, and then I will agree colonisation is of benefit, but I can't see one.”

MENTAL HEALTH AS RESISTANCE & THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CARE

On ‘Therapy’, Jimmy interrogates mental health not only personally but politically. “My mental health is probably a reasonable reaction to the things I've experienced and to the pressures and the lifestyle that I live.” He speaks about anxiety after COVID, the pain of a relationship breakdown, and the shame he internalised. But he’s open about the long journey: “I think people would find it really bizarre because when on stage, I'm quite affirmed, and when I'm with community, I'm affirmed, and I'll say what I think, but when it comes to the people I care about, I think I've always had a deep innate belief that I was unlovable, and it's taken 20 years to learn how to love myself.”

On ‘Therapy’ we find Jimmy at his most vulnerable, whilst having this yarn with Jimmy one thing that I was struck by was the vulnerability with which he spoke. He is aware that sharing the load of mental health, talking it out with others and allowing others in is how we can best overcome our struggles. “One of those things is taking my mask off, my persona, that Jimmy, that everyone knows, and let you see a little bit of the things that make me fallible, that make me not so perfect, and hopefully instead of judging me, you might see a little bit of yourself in it and feel comfortable for you to be able to be yourself.”

Jimmy is aware of the platform that he has to speak on but is reluctant to call himself a leader, rather he says, “We’ve got Elders, that’s their role, that’s not my role. When I speak, I speak on behalf of myself and, with the consent of the band, on behalf of the band.” But there’s no question that he carries a sense of responsibility.

His outlook is simple but demanding: passion and care. Care for his community, his band, and those who are pushed to the margins. “Mental ill-health can be seen as a reasonable response to a world that has so many systemic issues such as colonisation. There is not a problem with the individual but a problem with the world they exist in.”

That care begins with self-compassion and radiates outward. “You have to be as kind to yourself as you would to your friends. A lot of us aren’t, a lot of us are rigid with ourselves and hold ourselves to different expectations than we would hold our friends… You don’t speak negatively about yourself, nor should you. If you’re not cruel to yourself, then you’re not going to be cruel to others.”

Jimmy doesn’t claim to have the answers. He claims responsibility. He claims truth. He claims care. And he claims music as a weapon and a balm - a way to turn personal pain and political injustice into something larger than himself.

The music that Chasing Ghosts make is both catharsis and contribution. “I think a lot of the reason we make this music is we can make a contribution, and that makes it feel worthwhile and meaningful for us.”