The Blak Flâneur

An artistic essay accompanying the experiential exhibition Blak Flâneur

If you’d like to see the exhibition head to Bankstown Arts Centre before the 4th of March. You can find more information on their What’s On page of their website.

When I walk it is to be apart from society. It is to be and to see, to feel and to explore both myself and the world around me.

This exhibition, The Blak Flâneur has been, for me, the most difficult exhibition I’ve ever produced. It feels to me as though it is a thought that will not conclude, that the exhibition, in comparison to previous works, feels unresolved. A symptom of the larger theme of this body of work; this is personal in a way that I have never exhibited before.

In the past my art practice (at least the public work) has been largely visual explorations of a narrative with themes and ideas portrayed through characters as proxies to my own thoughts. I could espouse ideas through narrative and character that was at arms length from my personal identity. With Blak Flâneur I am publicly exploring myself and the way that I see the world.

So what is Blak Flâneur?

To be, perhaps, somewhat base, the term Flâneur is a French term (noun) referring to a person, literally meaning "stroller", "lounger", "saunterer", or "loafer", but with some nuanced additional meanings. Flânerie is the act of strolling, with all of its accompanying associations.

The term "flâneur" originated in 19th-century France and referred to an urban explorer, an individual who strolled through the city streets, observing society, and absorbing the ebb and flow of urban life. The flâneur was often associated with leisurely walks, contemplation, and a detached yet engaged observation of the cityscape. The concept of the flâneur was closely linked to the development of modernity and urbanisation.

Flâneur has also come to be a term applied to people (often to men - an issue that within this writing I won’t unpack) who wander, stroll and observe society in urban areas. Commenting on the society around them, making observations and critique. t has been co-opted by the design, architectural & photography community to be applied to someone who comments on society using design as a lens to, perhaps, make critique or documentation.

For the purposes of this work the characteristics of a flâneur are;

Observation and Detachment: The flâneur is a keen observer of urban life, architecture, and the people who populate the city. This observation is marked by a sense of detachment, allowing the flâneur to maintain a certain distance from the activities they observe.

Leisurely Exploration: The act of strolling or walking is central to the flâneur's experience. Unlike a hurried pedestrian, the flâneur meanders through the city, taking in the sights and sounds at a leisurely pace.

Urban Aesthetics: The flâneur is attuned to the visual and aesthetic aspects of the city. They appreciate the architecture, street life, and the overall ambiance of urban spaces.

Intellectual Reflection: Beyond simple observation, the flâneur engages in intellectual reflection. They may contemplate the social dynamics, cultural phenomena, and individual experiences that unfold within the urban environment.

Social Critique: The flâneur is often associated with a subtle form of social critique. By observing the city, its inhabitants, and their activities, the flâneur may comment on societal norms, values, and the impact of modernisation.

However, to fully understand the exhibition, we must apply the same thinking of etymology, usage and translation to the word Blak. We would first acknowledge the artist Destiny Deacon, who coined the term, and the exhibition curated by Hetti Perkins & Claire Williamson; Blackness: Blak City Culture. Blak is a term used by some Aboriginal people to reclaim historical, representational, symbolic, stereotypical and romanticised notions of Black or Blackness.

‘Blak’ is used as a cultural signifier by First Nations (Indigenous/Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander) people of the continent currently known as Australia. It is used to exemplify what it means to have an identity that is rooted in the First Nations community, an identity that is not tied to skin colour or blood quantum ideologies. It is used also to distinguish members of that community from other Black communities both locally and internationally.

I am personally ambivalent about the use of ‘Blak’ for the Indigenous community, of which I am a part, for a number of reasons:;

I question the need to have a ‘whole of community’ term and I disagree that there is a ‘whole of community’ (see discussions on Pan-Aboriginal culture and one size fits all approaches to working with First Nations communities)

We already have significant cultural and historical based terminologies that could be used, taken directly from individual community historical names i.e. tribal nation names

The community that ‘Blak’ is used to identify hasn’t been,for me at least, well defined and I have experienced situations where the term and the idea of a defined identity is weaponised - for example some attribute Blak identity to coming from poverty or other low socioeconomic signifiers

As an individual, I often push against any term of reference that defines me as part of a larger group. This may be a symptom of western influence on my ego or it may be a product of my upbringing. Not to get too deep into this point but, I want to have an identity that is my own and not be defined by expectations external to myself. I also find that the philosophical idea of being defined as part of a larger group leads to less importance given to individuals and their needs. (I touch upon this idea of needing to be defined as an individual while working for the betterment of the whole in another piece of writing in STAUNCH.). It boils down to the fact that, n the past, being defined as part of a group meant that I felt required to embody all facets and characteristics that defined that group. There being no clear cultural definition of those characteristics meant, for me, that I could not and would not be defined in such collective ways

Blak is, therefore, not a definitive term, and the sheer breadth of identities it can encompass makes it hard to contain, and understand fully. This makes it, at least to me, completely up for grabs to be defined and shaped as the community grows and changes.

As such, with the Blak Flaneur exhibitionI take what is mine for the taking and fI put forward that I am Blak and Blak/Blakness is me.

To that end,, I would like to propose my own definition of each term, as they apply to this work:

Flâneur [fluh·nuor] Noun.

someone who walks around not doing anything in particular but watching people and society and subsequently pondering and, perhaps, commenting on that society

Blak [blak] Adjective.

describing someone from Aboriginal, Indigenous, First Nations heritage who embodies the identity of that heritage as a perception and a core outward sign of their identity

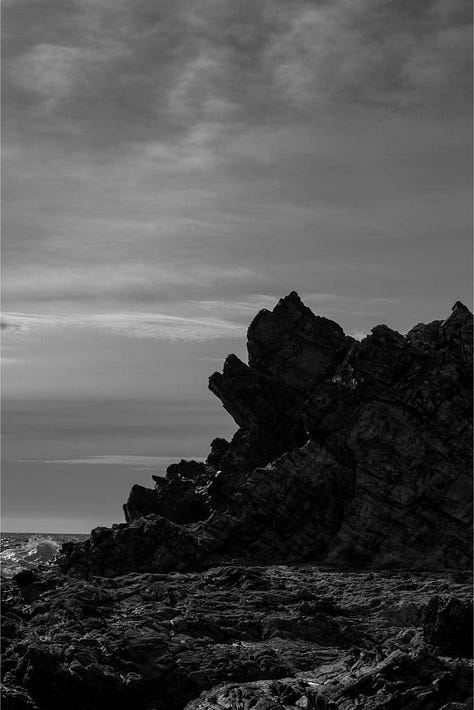

If you’re reading this while seeing the imagery used in the exhibition, you will likely notice that none of the works included are city, town or urban environments. I often walk streets in the city, particularly in Sydney and Newcastle as well as smaller towns and villages. After having lived in Sydney for several years through 2010 to 2016 I attempted a stint in Melbourne and lived there for several months. I would describe my time in Melbourne as a heightened version of my experience visiting, living & walking around modern cities.

I find myself in a state of anxiety and paranoia. The grid-like structures of the world around are antithesis to a human state of being. There is a lack of aesthetic cohesion. There is a cacophony of discordant noise, putrid smell, changes in temperature and my vision is assaulted by a constant disharmony of greys and steel hues mixed with light. Posters are falling down and torn, new posters are being glued. There are more people than the eye and brain can cope with for too long. There are quiet places of respite but they are also assaulted by a car or bus passing by high overhead or the grinding sound of a train's wheels on its track.

I won’t continue describing the negative experience of being in these spaces. I don’t find it amenable to walking and watching as a form of artistic expression that I would want to share with you in the way I am sharing this exhibition. I spend time in the city walking and watching, and also translating that into imagery through the use of the camera, but nothing I have to say is achieved by showing that imagery. Even in the semi-urban environment such as green spaces, I find that these are penned in versions of wild spaces. They are museum versions of the real thing.

A year ago, when I first started to put this body of work together, I decided to attempt to walk from Bankstown Art Gallery through to the Georges River along Salt-Pan Creek. It was not an enjoyable experience, nor was it an ergonomic ambulatory experience.

The creek and walkways that seem natural directions to me are blocked by fences, bridges that have been torn down and signs that say the way is no longer open. You turn a corner and there are piles of rubbish strewn or buildings where it seems as though there shouldn’t. For me this was a symptom of the problem of trying to exist in spaces that have been transformed by human hand and design but are not made for the purpose of human existence.

Prior to this moment I walked with an instinctual level of thought. Without analysis of why I walk where and how I do, to see and watch and observe the sights that I choose to see.

When I walk, my first inclination is to walk away from signs of humanity, I walk towards the natural and to leave the constructed environment behind. It is a navigation of my personal identity and my relationship to the world around me (space) and my place in that world (time).

Years ago when I first ‘revisited’ my artistic practice I left a version of a 9-5 job in Sydney and moved in with my father on a 100 acre property that shared a rear boundary with Wollemi National Park. I lived between there and Sydney for an 18 month period. During this time I was working in oil paint on large canvases creating experimental works for a show. I was also walking every day, at the back of the property into the national parks and into the deep woods.

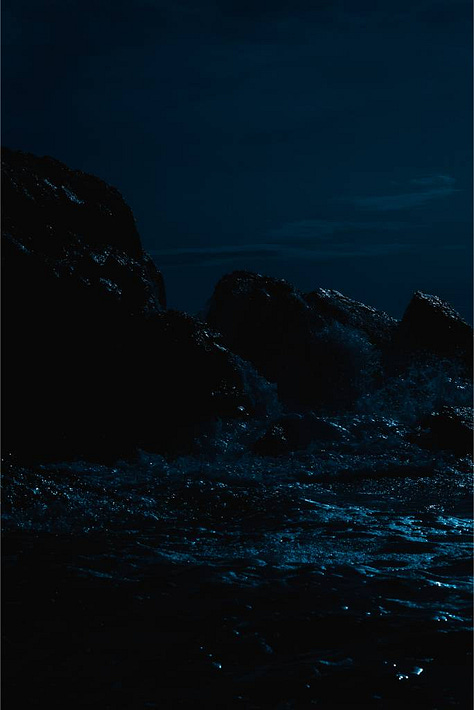

It is a place where there isn’t always a path. The rules of the human built environment don’t exist. There are patterns to find however they can be alternatively so vast or so infinitesimal that they don’t have a practical application for moving through space. I would follow animal trails and see where they took me.

I spend time around the edges of the built society and beyond that delineation. I walk during the early the late hours of light. I am deeply intrigued by observing changes in atmospheric conditions. When I walk I am searching for something, I do not know what that is. Each rise I pass over to see a hundred more trees is another leg on the journey.

This may seem like I am less of a flâneur and more hiker. I will leave that critique to you.

For me this is how I find myself in relation to society and it allows me a distance with which to compare the society I have found myself in.As a Gamilaroi person I was born into a society which does not recognise the legacy of my heritage. I am stripped of what would have been a part of my birthright if it weren't for the colonial interruption. A legacy of roaming, of access to wide open places.

I have a theory that all humans are the same - if we are to zoom out of the picture. If you have twenty people in a room and you are close to them, able to see their features, hear their individual stories, you see the diversity of experiences, characteristics and cultural markers. The further you are from those twenty people the less these differences stand out; one face looks much like the next, a large person is not that much different to a small person. If you zoom out further still the less these differences are visible, the less they matter.

When I walk I ponder not only my place in relation to society, I ponder how to cope with the world we are forced to exist in. I am apart from this society and a part of the problem of it, I contribute to the sum of human existence in my contributions to the degradation of the world around me and also to the artistic canon of humanity. I am a characteristic of everything that is good and bad about the society I observe.

I am Blak Flâneur

.

The Camera, The Microphone, The Pen & The other tools

The camera for me is an extension of what I observe. It is the best medium to capture a moment in time during a walk and freeze it in place. An image for me to revisit in the future and also a piece of art that translates the feeling I have when I am walking.

I will bring my cameras with me only when I go with the purpose of bringing them. They are usually the final step in the process of capturing what I have observed. Sometimes that will be the first time I have experienced a space but usually it is not. I will often walk a space several times before incorporating my cameras as tools to capture my perspective of space.

I use several cameras, lenses, film stocks and associated devices and mediums to assist with the translation of my vision.

The cameras used in this exhibition are:

Digital: Nikon Z5 & Nikon Z6ii with multiple lenses from the Nikon Z range.

For the majority of my landscape photography I use the Nikkor 24 – 200mm f/4-6.3 lens and for more specialised work I use the Nikkor 14-30mm f/4 S. I recently added the 24-70mm f/2.8 S lens and the 70-200mm f/2.8s into this workflow.

For portraiture work I use a range of primes and zooms including the Nikkor 35mm and 50mm f/1.8 S prime lenses and the 24-70mm f/2.8 S lens.

Film: Pentax 6x7 with the Super Takumar 105mm f/2.4 lens

My current main camera for medium format work is the Pentax 6×7 and I shoot the majority of the time with the Super Takumar 105mm f/2.4 lens and the SMC 45mm f/4 lens for wide landscape work.

I also experiment with Box Brownies, TLRs and other medium format cameras although I have chosen not to share any of this with you in this exhibition.

The film stocks used for this exhibition were Lomo Purple for the large vinyl prints.

Drone Photo & Video

My current drone kit is a DJI Mavic Pro 2 which has the Hassleblad 1″ CMOS Camera.

I have created High Dynamic Range images of each photo by shooting 5 of the same photograph and merging them together.

Audio

My field recording kit is a Zoom H8 paired with a Seinnheiser MKE 600. In the studio I use the Apogee Symphony and Rode Procaster broadcast microphones.

Paper

My fine art prints and photographic prints are done by Theresa at Fine Art Imaging in Balmain, NSW. If you’re ever getting work printed including digital imaging of original paintings definitely talk to Theresa, she is great.

Vinyl

The vinyl prints were printed by the team at Canterbury City Council.

Editing Suite

I work mainly across Adobe Suite for any visual work, particularly Adobe Lightroom, Photoshop and Premiere.

For audio editing and composition I use Logic Pro X

Plugins used for Logic are Izotope and Ozone

Some thanks

I would like to extend a huge thank you to both Rachael Kiang and the team at Bankstown Arts Centre for curating this exhibition, the support for an ambitious project like this is amazing.

I would like to thank my mother and father for their continued artistic growth throughout the course of my life - without which I would not have been able to do any of the things I managed to achieve.

A big thank you to the Awesome Black team who have encouraged and supported me in creating this work. What we are ankle to achieve together is amazing and being supported to put myself first in this way is incredible.

And a final thanks to Jade Goodwin, my fiance. Who is there, and listens when I tell her about my silly little idea or recount to her what I saw on my walk. You are the most supportive and intrinsically deep thinker, I am better for our conversations about art, form and outcome.